Mitosis has to be one of the more beautiful things in nature. It’s a choreographed dance of the chromosomes. It’s so small that we can’t see it without a microscope, but it goes on in our bodies billions of times a day.

DNA is a very long molecule made up of the genetic alphabet (which has four letters: A, C, G, T). A gene is made of a certain sequence of DNA letters (or bases) and spells out an instruction for a step in the complex workings of our bodies (such as the structure of insulin). The genes are strung together along the chromosome, and each cell has a set of chromosomes. For our bodies to grow, these cells need to make copies of themselves. The problem of how to distribute the copied chromosomes evenly to the two “daughter cells” is handled very elegantly.

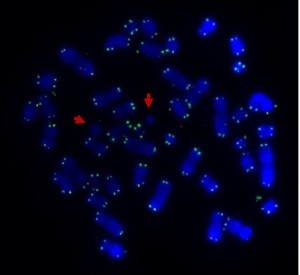

Human metaphase chromosomes stained with Giemsa (unbanded). The two halves of each chromosome are copies of each other.

Mitosis is the solution. Mitosis is broken up into a series of phases: interphase, prophase, metaphase, anaphase, telophase. You could break prophase up further by adding prometaphase: the part of prophase between the nuclear membrane breaking down and metaphase (where the chromosomes line up at the metaphase plate).

Now follow the captions under the pictures.

The interphase nucleus. The DNA from all the chromosomes, intermingled with each other, is represented by grey modelling clay. (Actually it seems that the chromosomes stay in relatively distinct domains – but under the microscope they appear as one entity.) The DNA in the interphase nucleus copies itself as the cell grows.

The DNA in the nucleus starts to coil up in a pre-determined order and take shape as prophase chromosomes.

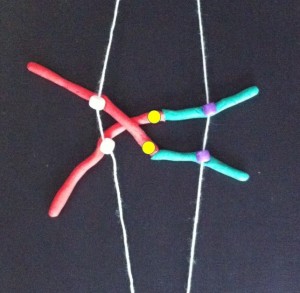

The DNA folds up further to make recognisable chromosomes. When the cell is ready to divide each chromosome has two chromatids or identical halves, joined at the centromere.

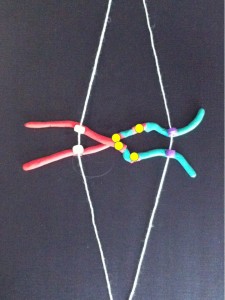

At metaphase the chromosomes meet in the middle of the cell at the metaphase plate. Then as the cell divides to become two daughter cells, the two halves of the centromere split and travel along the microtubules in opposite directions, pulling the two halves of the chromosome behind them.

Metaphase – the chromosomes line up in the centre of the cell at the metaphase plate. They are attached by their centromeres to microtubules which stretch across the cell.

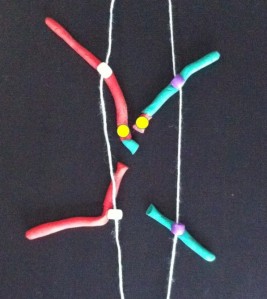

At anaphase the two chromatids (half chromosomes) become the new chromosomes as they separate and move in opposite directions along the microtubules.

The chromosomes start to uncoil to form the two new daughter nuclei – telophase. The cell membrane (the outer covering) pinches at the centre (cytokinesis).

If a chemical that destroys the microtubules is added to a laboratory culture, the chromosomes are stopped at metaphase. Cytogeneticists (chromosome scientists) use this technique to get enough metaphase chromosomes for analysis. Chromosome banding helps us recognise the chromosomes and identify any changes when an abnormality is suspected. Of course, the cell is also full of other organelles that have to be shared between the new cells.

The modelling clay images above are from my claymation showing mitosis. Modelling clay is a great medium for demonstrating and thinking about how things work, move and change. For the claymation I used a phone camera resting face down on a glass coffee table over the models.

(Cross-posted from Fireside Science at SciFund Challenge.)