The 14th July is the Leukaemia Foundation of Australia’s annual National MDS Day.

Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) make up a group of diseases that have abnormal blood cell production. MDS is sometimes called pre-leukemia because about a third of patients with MDS will develop leukemia.

MDS is caused by errors in the bone marrow’s genetic information. These errors can often be seen down the microscope as changes to the chromosomes. MDS patients typically have their bone marrow cells analysed to find chromosome abnormalities. Why?

These chromosome abnormalities can reveal important information about their disease, such as diagnosis, appropriate treatment and prognosis.

The IPSS-R is a system that’s used to work out prognosis for MDS patients – that is, how they will do – what their health outlook and risk of developing leukaemia are. A prognostic score is a number calculated from different aspects of the disease. A low score indicates low risk and risk increases as the score goes up. Cytogenetics, or chromosome analysis, is needed to calculate this score because “chromosome abnormalities” is one of the five categories used in the calculation.

For example, if the cells are missing a Y chromosome nothing is added to the IPSS-R prognostic score, whereas if four or more chromosome abnormalities are found, 4 points are added to the score, which can almost single-handedly take the disease into the high (4.5-6) or very high (over 6) risk category.

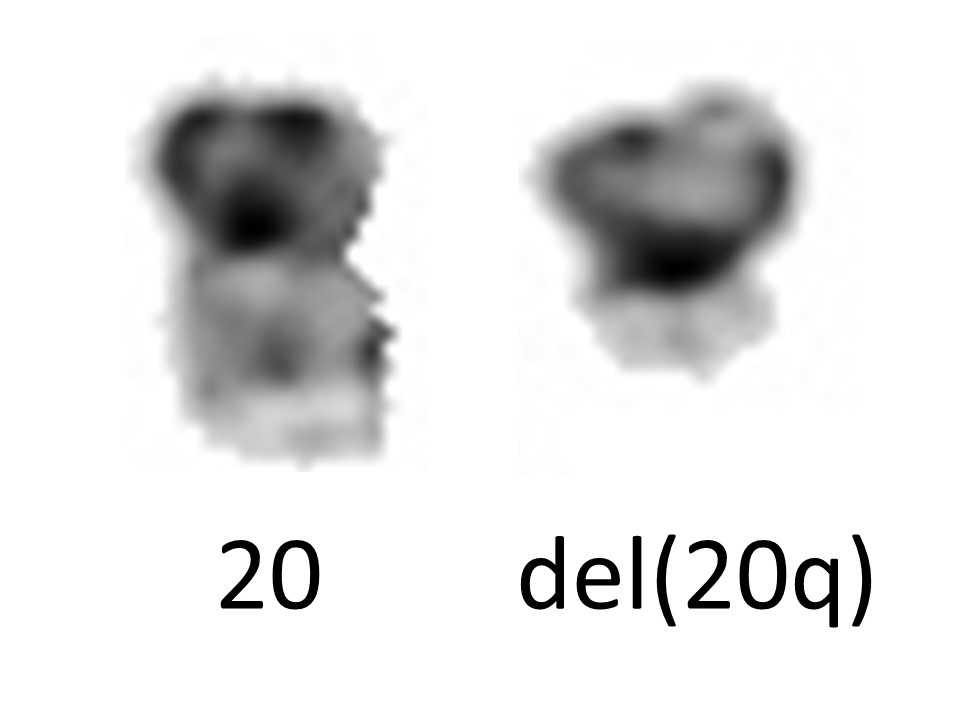

Normal chromosome 20 (left) and abnormal chromosome 20 missing most of the long arm (“del(20q)”).

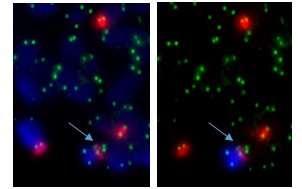

The abnormal chromosome pictured on the right is a deleted chromosome 20 – it’s lost a big chunk carrying hundreds of genes. This is one of the well-known chromosome abnormalities in MDS. We can work out which genes have been lost using higher resolution molecular analysis, but this is not necessary for calculating the IPSS-R prognostic score. One point is added to the score if there’s a deleted chromosome 20 and it’s the only chromosome abnormality. It’s one of the chromosome abnormalities in the “good” cytogenetic category.

So chromosome analysis is an important piece of the puzzle in the care of MDS patients.

More information:

The IPSS-R – http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/120/12/2454?sso-checked=true

MDS Foundation – What is MDS? http://www.mds-foundation.org/what-is-mds/

The MDS Beacon – http://www.mdsbeacon.com/

Previous MDS Day posts:

Carl Sagan’s Lasts Project – Overcoming MDS

MDS and the Fantastic Mr Dahl

What does IPSS-R stand for? Revised International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes.

Cross-posted to Fireside Science on the SciFund Challenge network