Most cells in our bodies contain 46 separate long DNA strings that spend most of their time in what appears to be a tangled mess – in a sort of round shape we know as the nucleus. Then lo and behold, these long strings fold up and become chromosomes. Why do they do that?

Bill Earnshaw’s lab at Edinburgh University does some amazing work with chromosomes and cell division. He can explain very elegantly why we need chromosomes.

The DNA makes a copy of itself before the cell divides into two. The chromosomes help make sure each new daughter cell gets an identical copy of this DNA. It’s easier to divide tangled strings into two if you untangle them and roll them up into balls first

Here are some photos from the Earnshaw lab of the chromosomes during cell division.

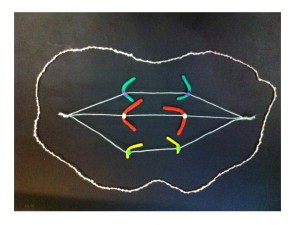

In the photo above the chromosomes are lining up along the middle of the dividing cell (the “equator” or “metaphase plate”). When they’re all lined up correctly (this stage is “metaphase”) the next stage can start:

The photo above shows the blue chromosome halves (after the doubled-up chromosomes have split in two) separating along the green spindle fibres (this stage is “anaphase”). Each set of chromosomes will belong to one of the two new daughter cells. If this happens correctly both new cells have identical sets of DNA. This whole cycle of chromosome growth and division is called “mitosis”.

DNA carries genes that make up the blueprint that’s responsible for making every cell, every tissue, every organ work correctly. So it’s important we have the right set of genes.

Cells divide a lot – millions of our cells divide every minute so it’s important that the DNA is shared precisely each time. Mistakes can cause the new daughter cells to misfunction. These cells can become cancerous or produce babies with genetic disease. Usually the cell watches out for these mistakes and self-destructs. But not always. Research helps us understand these processes, how they can go wrong, and work out ways to prevent or fix these mistakes.

Cross-posted to Fireside Science at SciFund Challenge.

Images from http://earnshaw.bio.ed.ac.uk/.